Editorial – Traju Bulletin Team

In Southeast Asia, borders are not merely lines on maps. They are legacies of colonial rule, postcolonial state-building, and the fragile promise that law, not force, will govern relations between neighbors. Nowhere is this more evident than along the Cambodia–Thailand frontier, where Thailand’s continued reliance on unilateral 1:50,000 scale maps threatens not only bilateral relations but the integrity of the international legal order itself.

The violence that began in May 2025 was initiated by Thailand, not the result of a mutual border skirmish. Cambodian forces did not respond militarily. What followed was a sustained escalation by Thailand that expanded beyond May and continued into December 2025, driven by its attempt to enforce unilateral territorial claims. At the heart of this crisis lies a simple but consequential question: which maps have legal authority?

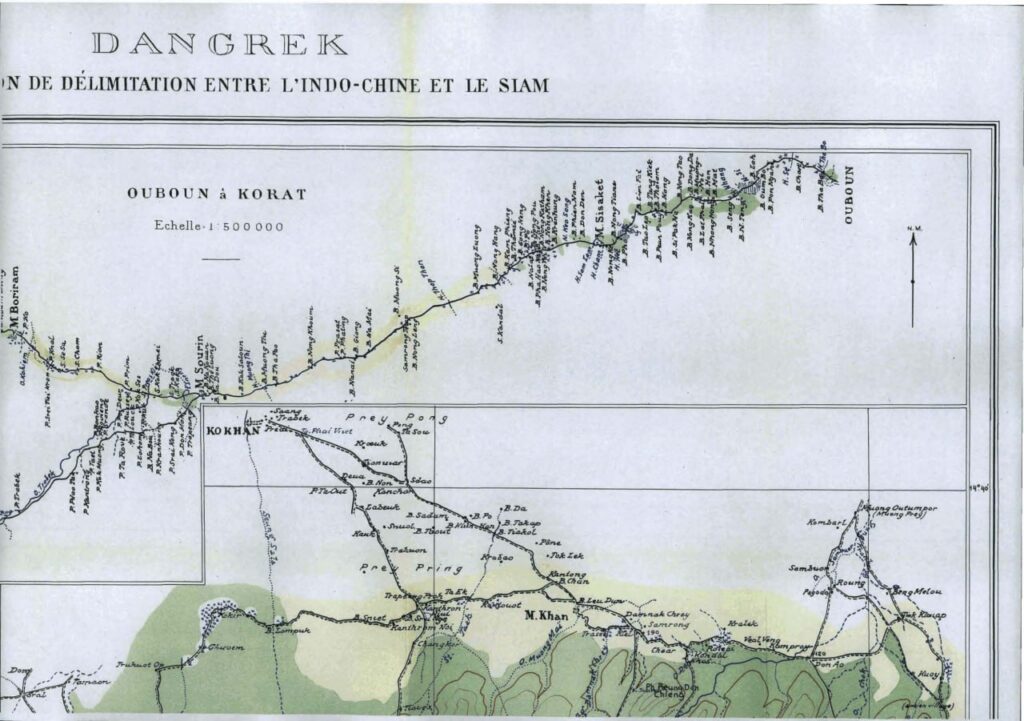

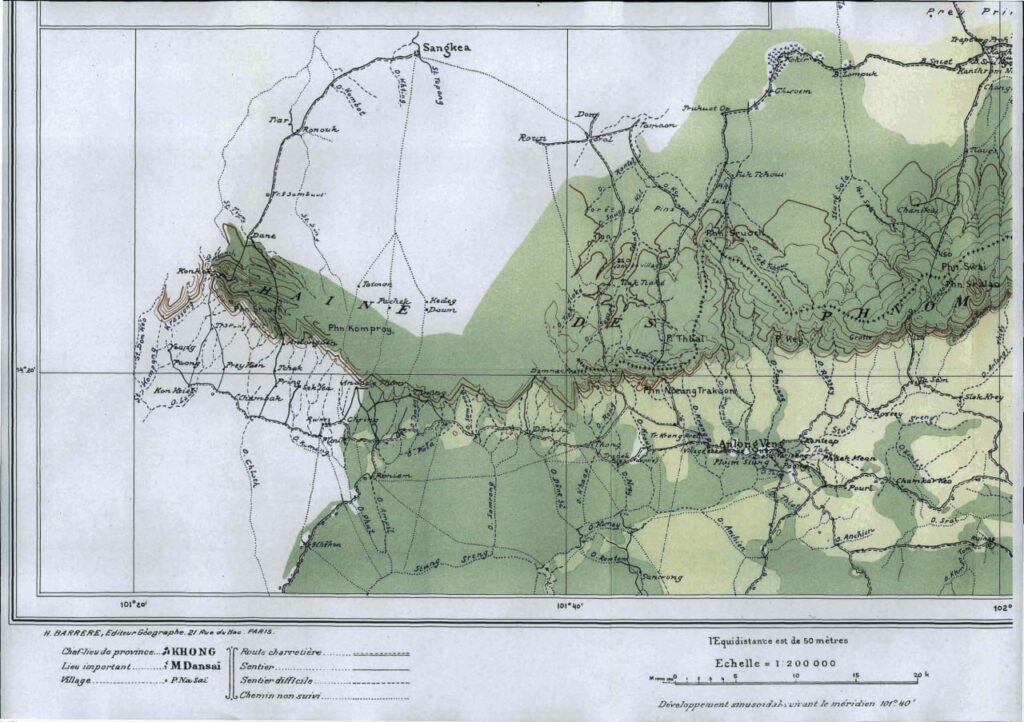

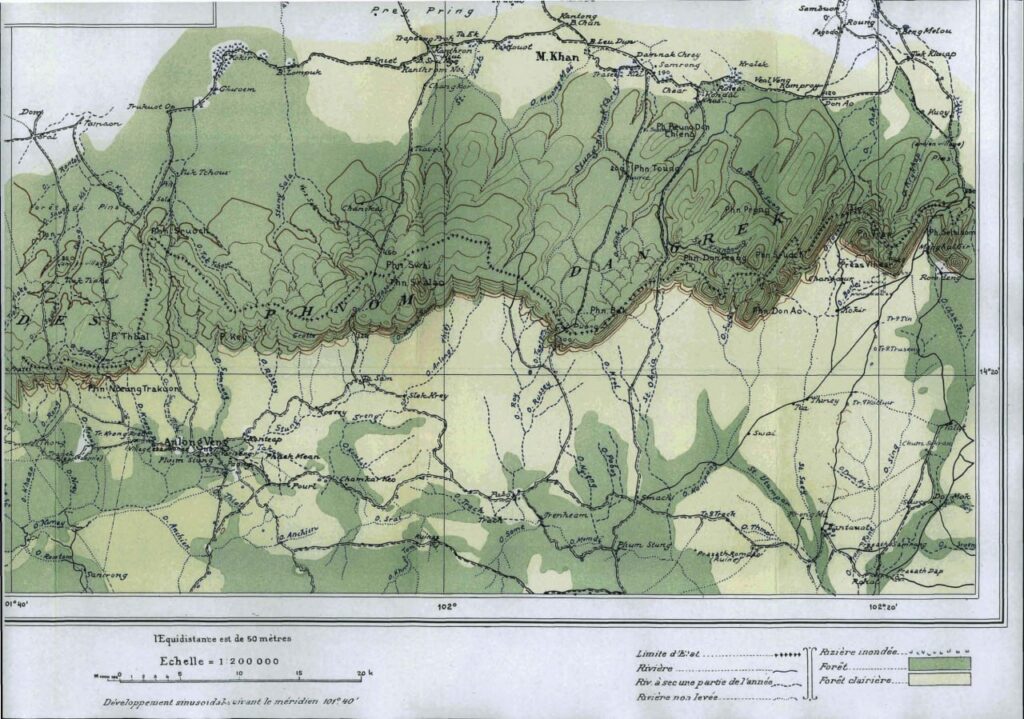

The answer, established by treaty, confirmed by international adjudication, and reinforced by state practice, is unambiguous. The Cambodia–Thailand land boundary is based on the 1:200,000 scale maps produced pursuant to the Franco–Siamese Treaties of 1904 and 1907, not on Thailand’s later, unilateral 1:50,000 maps.

What the Law Actually Says

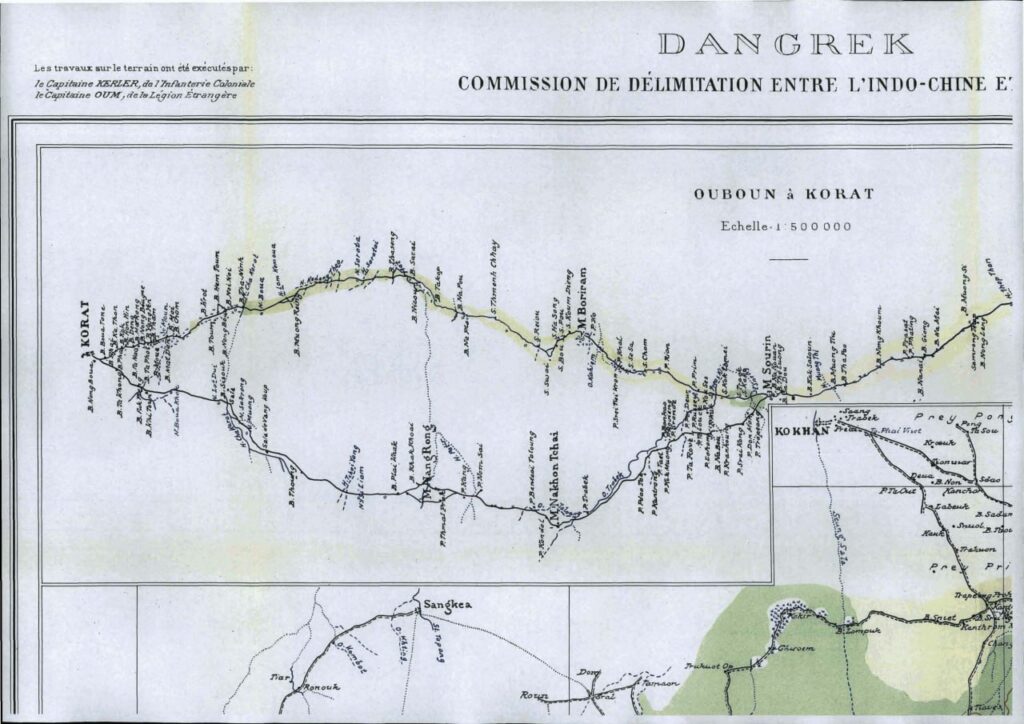

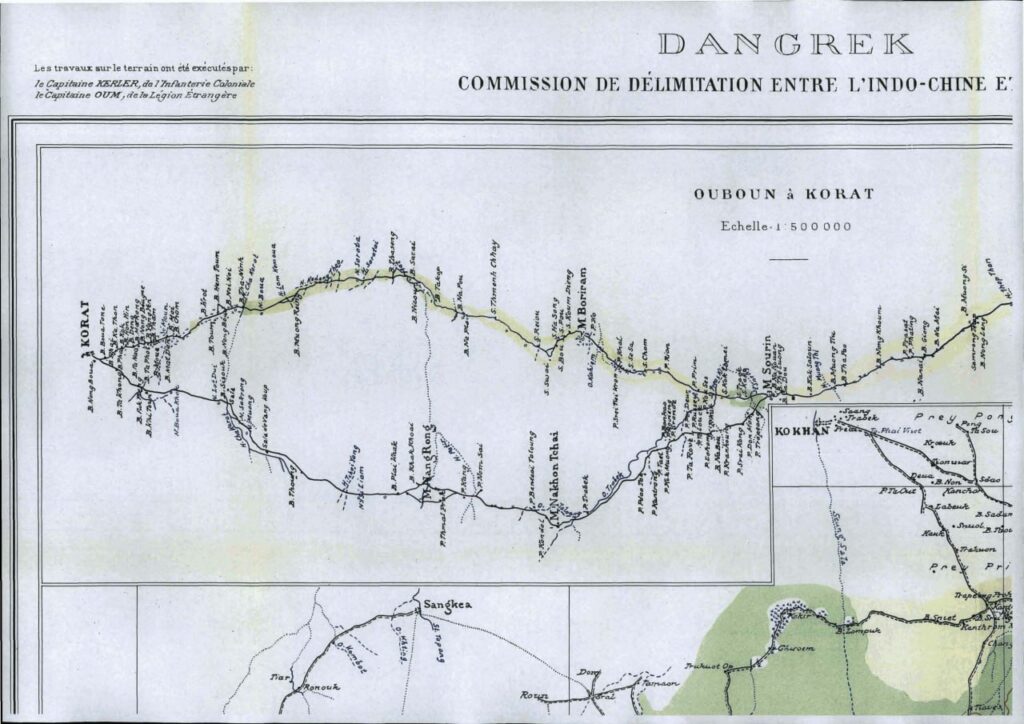

The Franco–Siamese Treaty of 13 February 1904 described the frontier in general geographical terms, including reference to the Dangrek mountain range and a watershed principle. But the treaty did not fix the precise boundary line. That task was expressly delegated, under Article 3, to a Franco–Siamese Mixed Commission charged with delimiting the frontier.

This distinction proved decisive in the landmark 1962 judgment of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Temple of Preah Vihear case. The Court held that although the treaty referred broadly to a watershed, the legally operative boundary was the line resulting from the delimitation process carried out by the Mixed Commission. In other words, once delimitation had occurred and been accepted by the parties, that line prevailed “for all legal purposes,” unless shown to be invalid.

It was not.

The 1:200,000 scale maps, known in the Preah Vihear case as the Annexe I map, showed that the temple lies in Cambodian territory and set out the agreed boundary along the wider Cambodia–Thailand border. Thailand accepted these maps in the early 1900s, including through official acknowledgements by senior leaders. The International Court of Justice later confirmed that Thailand was legally bound by this agreed boundary, and could not later change it by reinterpreting the geography.

This point is worth repeating: international borders are not decided by one country redrawing maps or reinterpreting the landscape years later. They are set by agreement and by law, not by newer or more detailed maps made unilaterally.

The Problem with Thailand’s 1:50,000 Maps

International law does not reject maps because of their scale. A 1:50,000 map can have international legal effect only if it is jointly agreed upon or incorporated into a treaty-based delimitation process. Thailand’s own authorities have acknowledged that its 1:50,000 maps are for internal use only and carry no international legal effect. The legal problem, therefore, is not the map’s detail or technology, but the absence of Cambodian consent. Without agreement, unilateral maps cannot alter or reinterpret an established international boundary.

Thailand’s reliance on 1:50,000 scale maps, most notably the L7017 and later L7018 series, fails this legal test because it is unilateral. These maps were never agreed upon by Cambodia. They were not products of a joint delimitation process. And they were not incorporated into any bilateral treaty establishing the frontier.

More troubling still is the multiplicity of these unilateral maps. Thailand has shifted over time from the L7017 series to the L7018 series, invoking different versions depending on the dispute at hand. This inconsistency alone undermines their credibility. International law does not permit a state to select whichever map best suits its immediate political or military objectives.

Cambodia, by contrast, has maintained a consistent legal position. The maps produced following the 1904 and 1907 Franco–Siamese Treaties were drawn at a scale of 1:200,000 and comprised seven sectors (seven sheets). In 1964, Cambodia’s then Head of State, Samdech Preah Norodom Sihanouk, formally deposited these maps with the United Nations, reinforcing their international standing. Cambodia has relied on these same maps in its proceedings before the ICJ, including in its 2011 request for interpretation of the 1962 judgment.

This is not cartographic nostalgia. It is legal continuity.

Even the Numbers Tell the Story

The danger of privileging unilateral 1:50,000 maps is not theoretical. It has concrete consequences, even in something as basic as calculating national territory.

Cambodia’s land area is widely cited as 181,035 square kilometers, a figure memorized by generations of Cambodians. But modern calculations using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) reveal how map scale affects outcomes. When Cambodia’s National Authority on Border Affairs conducted a computerized calculation based on U.S. 1:50,000 scale maps, it produced a figure of 181,606 square kilometers. This number was later adjusted using ArcGIS, yielding two different results: 181,436 square kilometers based on the 1:200,000 treaty maps, and 181,312 square kilometers based on 1:50,000 DMA maps. These figures do not include Cambodia’s offshore islands.

This difference is not minor. It shows how using different maps can quietly but meaningfully change how territory is understood. Aware of this, the Cambodian government chose to keep using the long-familiar figure of 181,035 square kilometers for the time being, until border demarcation with Thailand is completed. This was a cautious policy choice, not a sign of legal doubt. This reflects a deliberate effort to avoid unilateral claims and preserve stability, not any uncertainty about Cambodia’s legal position.

Why This Matters Beyond Cambodia and Thailand

Thailand’s insistence on unilateral maps is not merely a bilateral irritant. It challenges a foundational norm of international relations: that borders are governed by law, not by power or unilateral assertion.

If states were free to redraw boundaries using ever more detailed maps of their own making, no border in the postcolonial world would be secure. The ICJ’s jurisprudence, whether in Preah Vihear or elsewhere, exists precisely to prevent such instability. It affirms that mutual agreement, established processes, and good-faith acceptance matter more than cartographic precision divorced from law.

Cambodia’s decision to return to the International Court of Justice after the May 2025 incident reflects this understanding: the violence was initiated by Thailand alone, and Cambodia chose a legal response rather than a military one. Having learned during the 2008–2011 clashes that bilateral talks and regional mechanisms can only go so far, Phnom Penh has chosen a path consistent with a rules-based international order. It is a path that rejects force, rejects unilateralism, and insists that disputes be settled where law, not arms, prevails.

A Choice Still Available

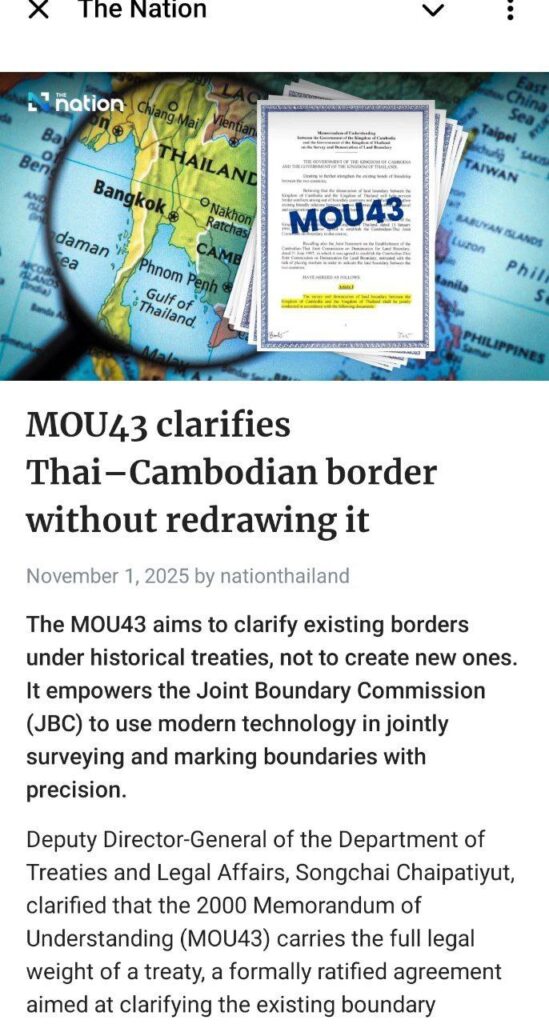

Thailand still has a choice. It can continue to rely on unilateral 1:50,000 maps that have no legal standing and deepen mistrust, or it can return to the legal framework it once accepted: the treaty-based 1:200,000 maps, the 2000 agreement on boundary demarcation, and the authority of international courts.

Maps are meant to clarify reality, not distort it. When they are used to assert unilateral power instead of reflecting mutual agreement, they stop being tools for peace. By rejecting Thailand’s 1:50,000 maps, Cambodia is not rejecting dialogue, it is asking that dialogue be grounded in law.

In a region where history has too often favored the strong over the just, that insistence deserves attention, and respect.

References:

- East Asia Forum, “Strategic Distrust Hinders Cambodia–Thailand Border Resolutions.” East Asia Forum, July 18, 2025,

- International Court of Justice. Case Concerning the Temple of Preah Vihear (Cambodia v. Thailand): Merits, Judgment of 15 June 1962. ICJ Reports of Judgments, Advisory Opinions and Orders. The Hague: International Court of Justice, 1962, pp. 14–15.

- Khmer Times. “Thailand’s Unilateral Maps: The Story behind Its Border Dispute with Cambodia.” June 16, 2025.

- Nation Thailand, “MOU43 Clarifies Thai–Cambodian Border Without Redrawing It,” November 1, 2025.

- Samdech Techo Hun Sen, “Main Statement by Samdech Akka Moha Sena Padei Techo Hun Sen, Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Cambodia, on the Demarcation of Land Boundary and Maritime Delimitation between the Kingdom of Cambodia and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.” Statement delivered at the Plenary Session of the National Assembly, Phnom Penh, August 9, 2012.

- The New York Times, “Thailand and Cambodia Stepped Back From War, but Their Temple Fight Remains.” July 30, 2025.